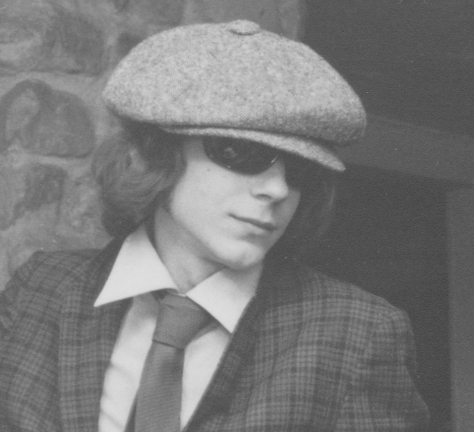

Writer and Eisner Award-winning editor Stuart Moore broke into comics in 1990 and has never looked back. He’s edited critically acclaimed books for Marvel and DC, and his writing includes comics and novels for a variety of publishers, as well as novelizations of comics and movies such as Civil War and John Carter. For AHOY, he and artist June Brigman have created CAPTAIN GINGER, a ferocious series about lionhearted cats in space. He’s also working on a new AHOY series for 2019. And his AHOY masthead title is Ops, which means he handles all the necessary publishing operations the rest of us are too stupid to learn. Stuart spoke from his home in Brooklyn.

AHOY: You know that Simpsons character called “Comic Book Guy?”

Oh yes.

Is there such a thing as the Comic Book Guy?

I think Comic Book Guy was intended to embody an old stereotype, as is a lot of the stuff on The Simpsons, at this point. That said, there are all sorts of people in the industry.

What are real comic book people like?

Well, one of the nice things that’s happened in comics in recent years is the broadening of the audience. When I went to conventions in the nineties, the audience was overwhelmingly male. Now, I’d say it’s half and half, which is really gratifying. It’s also much more diverse. The Internet kind of opened everything up.

Did the Internet change comic conventions, or was it the big super-hero movies?

They’re both definitely part of it. The super-hero movie thing has grown over time. In the nineties, you had the Batman movies, but that was about it. Then Marvel got into it with the X-Men and Spider-Man, and the Iron Man/Avengers movies started around 2007.

I think there’s a weird cycle to it. You have characters like Superman, created in 1938, who received notoriety on radio and TV shows, and then burst out as a big movie in the 1970s. The same happened with characters like Spider-Man and the X-Men; they were introduced in the early sixties, they had TV cartoon shows and then the big budget movies. There’s a certain point where a character peaks into the public consciousness.

Why are super-hero movies so popular?

A few reasons. One is that CGI technology finally caught up with the stories. Now you can have the characters do incredible things, it looks good, and you don’t even have to spend enormous sums of money. And because they’re successful, these films can command higher budgets.

I also think it’s licensing. Marvel licensed out the rights to X-Men and Spider-Man to different studios. You had them competing to keep the rights by pushing out films, and that sort of saturated the market. This wouldn’t have worked if the movies weren’t good, and people didn’t like them. As for the cultural shift, I’m not really sure what brought that about.

When did all the cosplay start at Comic Cons?

It’s always been there, to some degree. I think it kicked into high gear when Manga became a major part of comics fandom, around the turn of the millennium. That brought in younger fans who were serious about cosplay. But as far back as the seventies, you had people in super-hero costumes. And in the nineties, you had a lot of Klingons.

What do you make of people who dress up?

I think it’s all very cool. People come to the cons specifically to see the costumes, now.

Ever get creeped out by people who go too far?

There was the band, GWAR, that used to go to comic conventions, back before a lot of the cosplay. They’d walk around in full costume and squirt goo at people. That was a little much.

What is your favorite all-time single comic?

There was one that I think of as an incredible masterpiece. It’s an issue of Jack Kirby’s New Gods called “The Glory Boat.” Kirby was an acknowledged genius; he co-created most of the Marvel super-heroes. But on his own, he wrote and drew the “Fourth World” cycle in the early seventies for DC, and I was just the right age to read those books. They’re kind of insane. The writing style is overblown. The characters don’t talk like human beings, and every word balloon tends to have three or four exclamation points.

Kirby had fought in World War II, and here he was writing about gods who come to Earth. In “The Glory Boat,” the main characters are godlike beings engaged in a savage war that is chewing up the world. In the middle of it, you have three shipwrecked people—an old war veteran, and his son and daughter. The son is a conscientious objector. What happens is terrifying, and with Kirby—a fast and prolific artist working in the moment—you could see his trauma seeping out onto every page. It hit me, as a kid. I still have the copy that I bought. I re-read it the other day, and it’s just as powerful as I remember it. What does war do to you? IT TAKES AWAY YOUR FACE.

Have comics become simply a mechanism to create movies?

No. I don’t think that’s true. In fact, I think when they are designed to create movies, they usually fail. What has happened is that Hollywood has noticed them as source material.

Your book, CAPTAIN GINGER, is about super-evolved cats in outer space. Why has nobody ever before done that?

You know, I’m mystified. Go to Google Image Search, you see page after page of cats in space suits, but try and find stories about them…

Where did the idea come from?

Well, I created it for June Brigman, the artist. She and I were working on a comic called THE 99. We had a scene that was supposed to be in a cat sanctuary, and June just drew cats everywhere—in every corner of the panel, fighting each other, climbing on things, climbing on people. I looked at that and I thought, There must be something we can do here. I love cats, and I love outer space, so it just kind of grew from there. June loved the idea, and we spent a few years just playing around with it, until AHOY came along.

You’ve done adaptations of all sorts. What’s the trick?

I’ve done novelizations of film scripts and comic book stories. I’ve adapted film scripts to comic books. Much of it depends on length. When you’re adapting to comics, you never have enough space. People always want an adaptation that matches the movie as closely as possible, and they want it done quickly.

The hard part with novels, I find, is viewpoint. When you write in prose you tend to pick a character and stay with their viewpoint. But a lot of comic books and films shift viewpoints constantly—especially action movies. Old comics did that even more, with thought balloons. When you adapt that stuff to another medium, you have to make decisions.

Can you leave your own mark on the story?

It depends. When I wrote the novelization of the movie John Carter, I felt the need to be quite faithful to the script. With the Marvel novels, sometimes there’s a little more leeway, and that is, frankly, out of necessity, because some are adapted from old stories that need to be updated. The characters have mobile phones now, that kind of thing.

In the adaptation of Civil War, one decision I had to make was how many characters to use. The movie involved virtually the entire Marvel super-hero cast, and I didn’t want to put off casual readers who might not know all the players. Then again, it was called “Civil War” for a reason. Without a certain critical mass of characters, you have no war, just a fight between Iron Man and Captain America. So you make decisions.

When you do a novelization of a big movie, do you get the script in advance?

I’ve done direct adaptations of John Carter and of the 2011 Conan the Barbarian movie. In both cases, they sent me an advance script. For John Carter, the script arrived with my name watermarked across every page. Each page also had its own unique identifying number and a hologram of Mickey Mouse’s head, which I assume would send some signal to Disney if it got within 20 feet of a photocopier.

That’s pretty intense.

They’re security-oriented. It’s fine, it’s just the world we live in.

To be successful, what does every comic book need to deliver?

I don’t believe in rules for writing, but I think every comic book should have one moment that hits you in the gut, something that makes you go, “Whoa!” It can be a tear-jerker moment, or the funniest thing you ever read, or a plot twist you never saw coming. There are a thousand ways to do it, but none are easy.

What makes super-heroes so popular? Why do we like these people, when in fact, some are jerks?

I think there’s something that clicks into your psyche and works as a power fantasy. It’s something you live through vicariously. You think, “Wow, that would be cool!” It can be a positive thing, where you’re Superman pulling a cat out of a tree. It can be a vengeance fantasy, like the Punisher mowing down killers. It can work in many ways.

I think the reason so many people responded to Wonder Woman was that scene where she’s told that nothing can be done, that we can’t save these people in the war, and she refuses to accept that. She plows forward. She decides, we have to do something! And then she does. That’s what people responded to.

In some way, you need to be with that character as they take the decisive action. And by the way, that is a very American thing, where we think of one person making a difference. It’s central to our national system of beliefs.

Okay, time for The Lightning Round!

Hmm, okay. *cringe*

Your greatest all-time villain:

Villains are hard. It’s probably… the Joker. Or maybe Thanos. I wrote a whole novel about him.

The super-hero you wouldn’t like, if you knew him close up:

I love Batman, but he would be insufferable. He’s sour as hell, and he’s a zillionaire.

The worst super-hero romance:

You mean, worst couple?

The two people who just shouldn’t be together:

In the late eighties, there was a flirtation with getting Superman and Wonder Woman together. That was bad from start to finish.

Capes:

Capes?

Yeah, what’s the point?

I haven’t given this much thought. But a lot of super-hero costumes are derived from circus performers. Visually, the only cape that really works, I think, is Batman’s. It can be drawn as this billowing thing that fills the sky.

But if you drive a Batmobile, isn’t a cape the last thing you need? Every time you get in, you have to spread it carefully, or it’ll bunch up.

Well, yeah.

It’ll crinkle up beneath you.

It’s 100 percent impractical. The way Batman’s cape works is complete fantasy.

Worse, it would catch on the car door. You’d jump out, take a step and hear your suit tear.

We used to say that villains would stomp on it, so he couldn’t move. But look, there’s something you should realize here: It’s not real. These stories aren’t actually happening.

Shouldn’t comics have a real-life component?

We used to discuss this at DC. In the eighties and nineties, it was very much in vogue to make heroes realistic, to show them in the real world. Marvel had a line called The New Universe that was all based around that idea.

The goal was to make characters more relatable for the reader. But if you take things too far, you run into absurdities. I mean, Superman’s powers will never make sense. If you try to make it too real—I mean, to figure out how his heat vision works, or how Batman gets out of his car with that damn cape—at a certain point, you take all the fun out of it. So I was happy when the pendulum swung back the other way.

We used to say that every comic has an unlimited budget: that if you can imagine it, and someone can draw it, then you can do anything. Now, with CGI, the movies have caught up a little, but there is still something wonderful about the wide-open page. With a canvas like that, why would you want to be constrained by the laws of physics?

The blank page.

Yeah, the blank page. It’s terrifying, and it’s exhilarating.