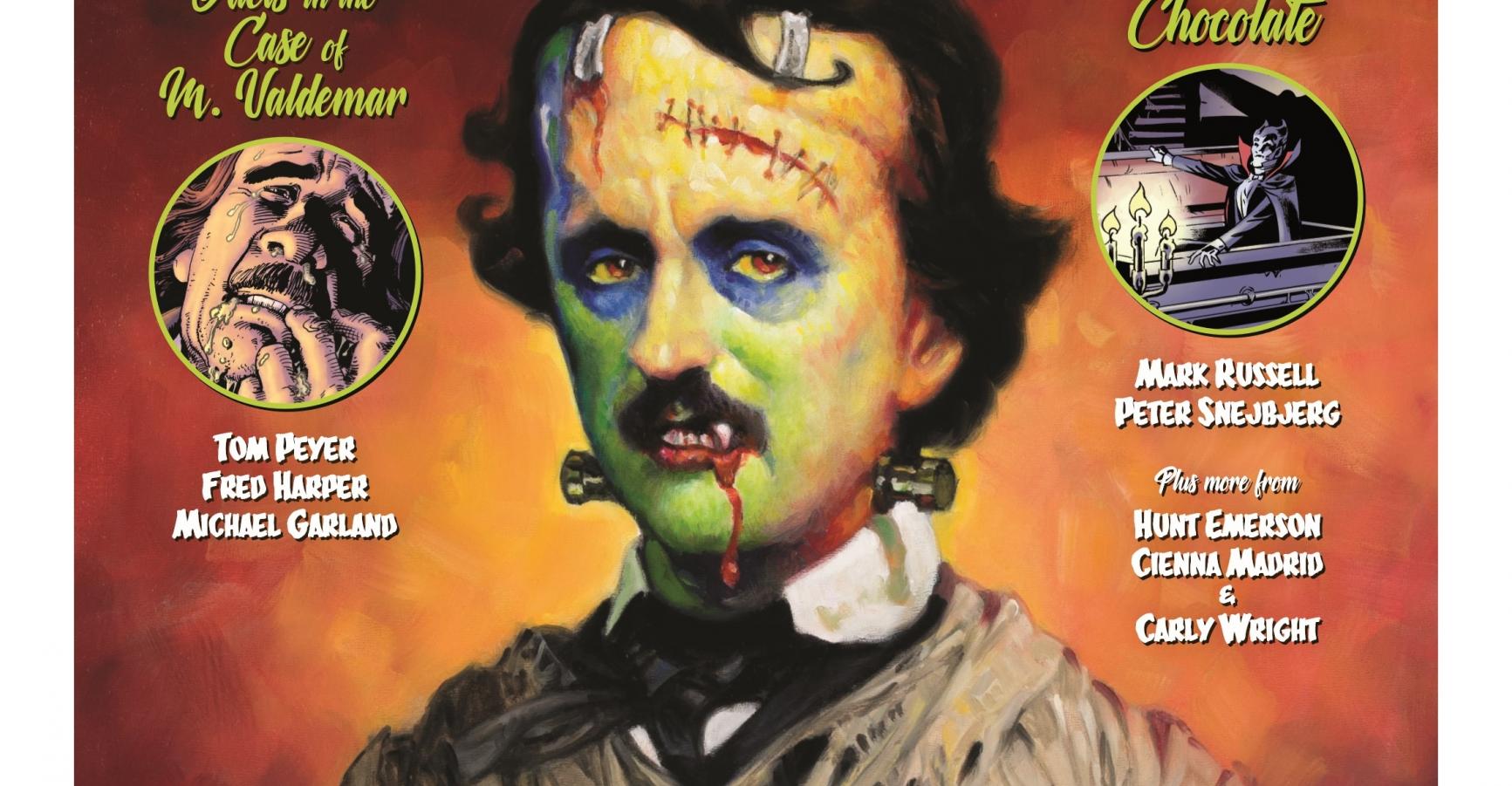

In 1976, Tom Peyer launched a weekly comic strip for the Syracuse New Times, an alternative newspaper in Central New York. Twelve years later, he became an editor at DC Comics and then a writer with more than 250 titles on his bibliography. His newest creations – HIGH HEAVEN and THE WRONG EARTH – offer crisp, hilarious send-ups on religion and the superhero genre. He spoke with Hart Seely about his life, his career, and the ways of comics.

Q: What’s the first comic you ever fell in love with?

It was Superman, No. 140, which came out in 1960, a long, involved story, “The Son of Bizarro,” which took up the whole issue. It was this mad, crazy soap opera, where Bizarro Superman and Bizarro Lois, on their Bizarro world, have a son who comes out human. It shocks them, and they very sadly send him to Earth to live among humans. He ends up in an orphanage with Supergirl. Eventually, he turns into a Bizarro; it was a delayed change – like a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. The Bizarros get wind of it and send an army to take back the baby. What a great story. I still read it sometimes.

Q. Wow. How old were you at the time?

I was six. I had read comics before it. I had seen Superman on TV. But that was the one that made an impression.

Q. Bizarro world is a heavy concept for a 6-year-old.

Yeah, the idea of a duplicate of yourself, which comes from you, being so powerful and stupid… It must be how every parent feels.

Q. As a kid, how did you get your comics?

My mother or father would bring me on trips downtown (Syracuse) to do business. I would beg for a comic, and they would get me one.

Q. Were you the kid always drawing in school?

Yes. I would get in trouble for drawing in my schoolbooks. I would draw while listening in class, but the grownups never understood.

Q. Did you have a mentor, an adult who pushed you towards drawing?

No, I just wanted to do it. Superman on TV led me to the comics, which led me to drawing. My parents didn’t have much, but comics were cheap, and they both encouraged my love of drawing. I didn’t really have art supplies, but there were things you could find - God, I sound like an old man – like shirt cardboards, the thin pieces of cardboard that came in a shirt package. They were like Bristol Board, they were great.

Q. Did you do well in art class?

No, terrible, because they didn’t want me doing what I wanted to do. They wanted me cutting out pictures and pasting them neatly onto things, and I couldn’t follow the curriculum. I was a disaster.

Actually, I was a good student until midway through elementary school. I just got discouraged.

Q. When did you go south in the educational system?

It was a gradual south-going, which probably started in third grade and gradually pitched downward. I was picked on, pretty much. I was lonely. The comic books came in handy.

Q. Did you draw superheroes to get back?

They felt like my friends. I think that’s part of their appeal, especially with secret identity superheroes. If you read their stories, you’re the only one who knows their secrets. That makes you closer to Superman than even Jimmy Olsen or Lois Lane. You’re like his real best friend.

Q. You see his thoughts.

Absolutely. In fact, in the fifties, they would often end Superman comics and TV episodes with Superman winking at the reader or the viewer – winking directly at me.

Q. When did you start to see yourself as a writer?

When I found out how hard that doing adult, professional drawing was.

In my twenties, I started doing a regular strip for the Syracuse New Times, an alternative news weekly. I had to draw pictures and write jokes. After a while, it seemed like writing jokes was the thing I did better.

Q. How did you land that job?

A friend named Frank Malfitano was writing for the New Times. Their cartoonist left, and Frank set me up for an interview with Ken Simon, the owner. But I didn’t get the job. Instead, he gave it to Al Roker, who was going to college nearby.

Q. Wait… THE Al Roker?

THE Al Roker!

Q: You kidding?

I am not kidding. The Al Roker who, by the way, claims he does not remember doing the comic strip. He didn’t last long, and Ken gave me a nice big space on page two every week. I learned how to do it in public, while doing it. And to this day, I curse the name Al Roker.

Q. From that strip, you moved to DC Comics.

I had done the weekly strip, along with a superhero comic with Joe Orsak called “Captain ‘Cuse.” I did some of the writing, and nearby in Ithaca, Roger Stern - a bona fide Marvel-DC comics writer - was one of our readers. He became overcommitted and needed someone to help him. That’s how I broke into the scene. I became an assistant editor at DC under Karen Berger, one of the great editors who has ever lived.

Q. Are comics evolving, or are they just as they always were and always will be?

Oh, no, they’re always changing. If you compare comics from different decades, the differences will be striking. Kids grow up and become artists and writers, and they put into comics all the things they thought were missing when they were young.

Q. Is it positive change?

It’s like everything else. Some of it is a wonderful addition, and some is just ruinous crap. It’s not like an army marching in lockstep in one direction, but more everybody bringing their own concerns and peccadillos.

Q. What’s the most positive change you see these days?

That it’s not just white men doing them. That is the single biggest piece of good news in a long time. People who are not just straight white men – they’re not just getting in the door, but they are in demand, which is great. Aside from the fairness and social justice, which are important, comics tend to calcify from generation to generation when there are no other voices – just white guys who’ve read comics their whole lives. That’s when stories become shallow and dull. Different points of view are what keep it alive.

Q. Is the wild success of Marvel and DC movies helping or hurting comics?

Sometimes, you can’t really know the impact of the evolutionary period until it’s over. The movies are certainly making money and bringing attention to the characters, but I don’t know if it’s having an impact on comic book sales. It’s hard to know, except that we get to keep doing them, because somebody somewhere is making money.

Q. Will the genre will continue to grow?

We just had two billion-dollar superhero movies within three months of each other. I don’t know how big it’ll get, but they’re not stopping any time soon.

Q. Are they good for America, or are they becoming something else?

Well, I think they’re more progressive than westerns were. I can’t imagine anything more reactionary than a western.

Q. But the age of westerns was 40, 50, years ago.

True, but it’s another case of a single genre that was dominating the field. Either way, I don’t think Hollywood genres are ever going to be the thing that saves us. None of them seem all that progressive. Actually, on that front, I think superheroes are doing pretty well for themselves. I look at Thor: Ragnarok or Black Panther, and I don’t feel they’re reactionary. Now, Batman Vs. Superman, on the other hand, that was reactionary.

Q. Some superhero movies are basic modern westerns, don’t you think? Wasn’t The Magnificent Seven just a version of The Avengers?

The great American albatross is the Good White Man with a Gun. Historically, that is what has driven our imaginations, and it’s the thing we make fits and starts to try to get over. There will always be parallels between superhero movies and the Good White Man with a Gun. But there are also opportunities to break away from that.

Q. Will there be another breakthrough superhero, or are all the main characters already taken?

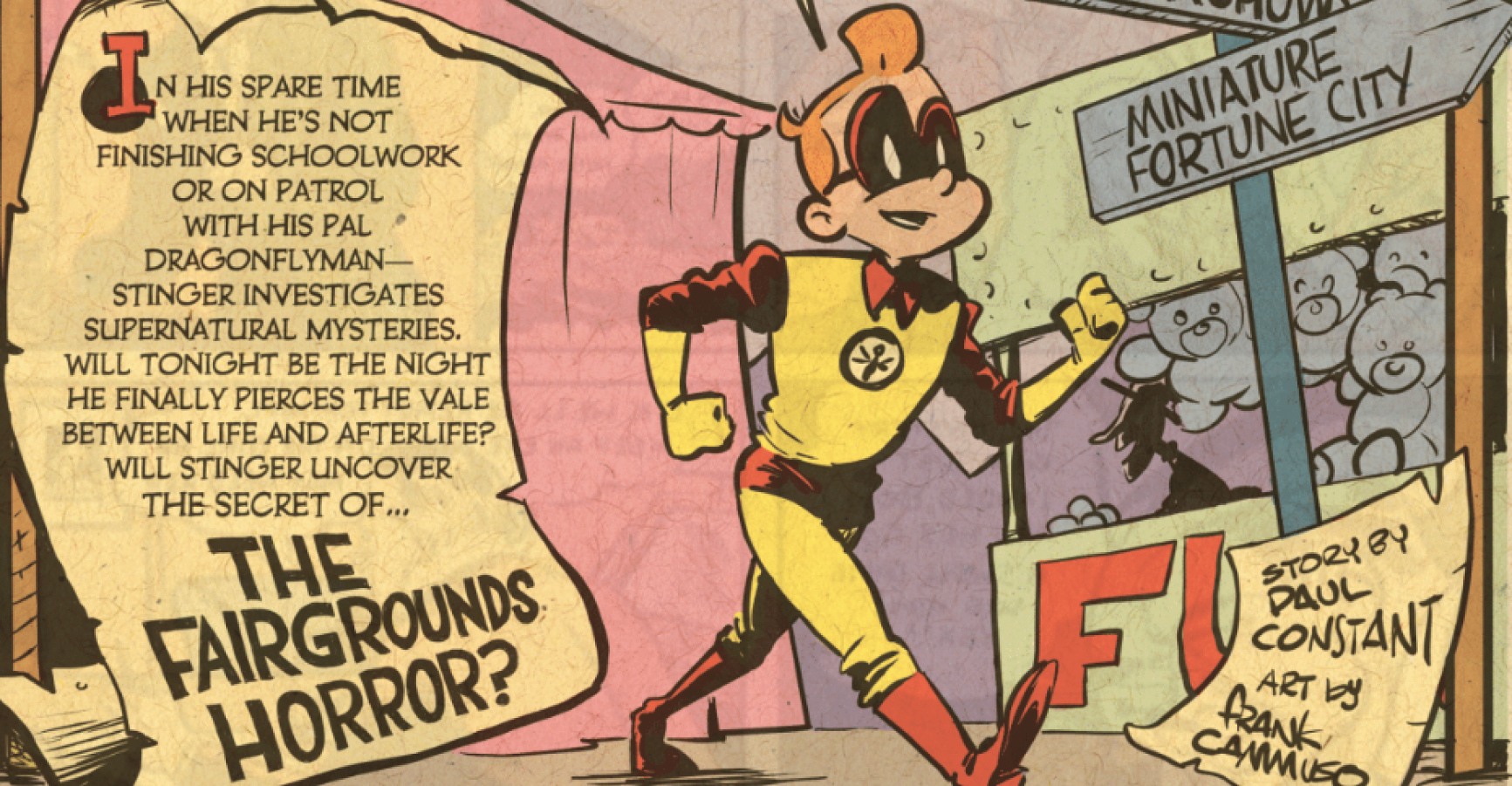

It seems like readers go for established characters, or variations on them, and tend to ignore new ones… a lot. Some assholes who are against diversity in comics will say, “If you make Thor a woman…” or, “If you make Iron Man black, you’re stealing our characters.” But enough fans only seem to care about character names and costumes that already exist, so the big companies have to do it that way if they want a diversity effort that anyone will notice. We’ll see what happens when they read The Wrong Earth.

Q. A new character with a completely new switcheroo.

We’re obviously going to lose our shirts on this.

Q. Would DC or Marvel have done The Wrong Earth?

Maybe, but with their own characters. That would have been the smart way to do it.

Q. Who is your all-time favorite comic book villain?

Villain? I don’t like villains, they’re evil.

Q. Come on, you must have a favorite.

I’ve got to say that I’ve always been entertained by Doctor Doom. He is the best, because everything is based on his one character flaw: He’s got to be Number One, the best, but the fact is… Reed Richards is smarter than he is.

Q. With the mask and cape, the first time I saw Darth Vader, I thought, “Doctor Doom!”

You must have been thrilled to see Doctor Doom on the big screen.

Q. Who wouldn’t be?

I would not want to spend a minute with a person whose heart is so dead, that they wouldn’t be thrilled to see Doctor Doom on the big screen.

Q. No villain comes close.

And he’d be the first to tell you that.

Q. Who is the one superhero you would dislike knowing in real life?

Aww, jeez…

Q. The quick answer is Tony Stark, right?

If he were a presence in my life, I would probably get sick and tired of him. But I don’t think I would get along with Hawkman.

Q. Why Hawkman?

I can’t see myself hanging out with Hawkman. When Green Arrow became the house liberal at DC Comics, Hawkman was always bickering with him. Hawkman, due to his reincarnations or his role as an interplanetary police officer, leans pretty far to the right.

Q. Don’t most of the modern characters have much larger personalities than Batman or Superman?

When we were kids, that was a fair statement, but comics change over the decades. If you’re talking about the Silver Age of Comics, yeah, the Marvel characters were more about personality. Superman was like Seinfeld or Andy Griffith, in that he was sort of the calm, slightly boring center of a world full of crazy-ass characters. I think that was a good way to handle it.

Q. I want to turn to an old debate: Would Batman let Superman drive the Batmobile?

Superman has absolutely no reason to drive the Batmobile. Superman can fly. This would never come up.

Q. But Superman the most dependable hero in the world. If he wrecks the Batmobile, he’s going to fix it.

I cannot foresee a scenario where Batman – unless he were brainwashed by a villain – would say, “No, Superman, I do not trust you with the keys to the Batmobile.” He would never say that. But why would Superman need the car?

Q. Why did Fred Flintstone need a car? There are times when arriving in the Batmobile makes an impact.

Landing from the sky with your big red cape, that’s a pretty good entrance.

Q. But we agree: Batman would hand the keys to Superman if the moment called for it.

He wouldn’t hesitate. You’re right.

Q. This an obscure debate. I mean, what other superheroes had cars?

Ghost-Rider has his bike. Green Arrow used to have the Arrow Car, but that was when everything about Green Arrow was imitating Batman. He had the Arrow Cave, the Arrow Signal and the Arrow Car. It was embarrassing.

Q. How did he get away with that?

They were owned by the same company.

Q. Didn’t Aquaman have an underwater chariot?

I’m thinking of something pulled by seahorses. Spider-Man had a Spider-Mobile in the seventies. It could drive up sheer walls, and – also in the seventies - Superman had a Super Mobile, which was an airship with robotic fists that would punch villains. They both had cars for the same reason. Can you guess what it was?

Q. I have no idea.

So they could sell them as toys.

Q. Think you’ll ever invent a superhero who sells toys?

Dragonfly and Dragonflyman. I probably won’t live to see the billion-dollar movie about them, but it will happen. You know, this has been fun. We haven’t even talked about the Yankees.

Q. They’re going to win this year.

They’re going to win it all, and Ahoy will be a smash hit. October will be the greatest month of our lives.

Q. What if the Yankees fall apart, our comics tank, and Trump wins all the elections? What then?

Suicide pact.